Alright, let's see it!

(Yes, I know some of y'all prefer "All right")

What Am I Doing Here?

Sometimes my social media preparations or interactions result in ideas or arguments that are a little too wordy or complex for the type of content I usually create, so I thought I would create a Substack so I can be incentivized to publish some of these thoughts or responses. I don’t know how frequently these posts will be published, but I’ll try to ensure it averages at least one or two times a month. This first post will be public, but I’m not sure how I’m going to curate things moving forward.

A Response to Jonathan McLatchie

In this first offering, I’d like to respond to Jonathan McLatchie’s response to a video of mine where I criticized attempts by Sean McDowell to gloss over contradictions in the Gospels’ accounts of the resurrection. McLatchie’s response is somewhat unique in that he claims not to hold dogmatically to a doctrine of inerrancy (see his comments on inerrancy here), but he does go to great lengths to try to sidestep the problems with the differing accounts of the resurrection. He seems to be more dogmatically opposed to the conclusion that the Gospel authors made “assertions that are contrary to what they knew to be true.” He says he doesn’t “believe the evangelists ever intentionally altered the facts.” That may very well be true (or it may not be), but that doesn’t necessarily have any bearing on my concerns unless one just presupposes the authors of the Gospels knew for sure precisely what happened on the morning of the resurrection. I don’t think there are any data that make such a conclusion most likely. If they didn’t have sure knowledge of what happened (the data indicate they didn’t), then the discrepancies aren’t necessarily the product of intentional alteration of the facts. It seems to me I’m still running up against a dogmatic response on the part of McLatchie, and I think that will be further borne out in the course of this response.

After quoting a statement of mine to the effect that McDowell is taking a dogmatic stance, McLatchie responds:

McClellan appears to misunderstand the nature of our approach. The high reliability of the gospels and Acts is the conclusion of our argument, not the premise. We do not decide ahead of time that the evangelists did not make things up or intentionally alter the facts. Rather, this is the verdict we have arrived at after careful and extensive study of the data.

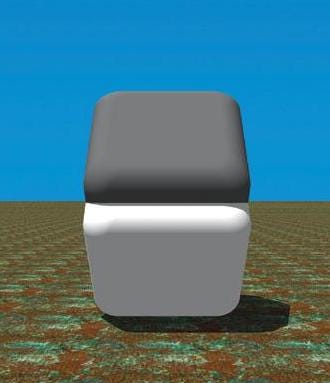

I have no doubt that McLatchie believes this to be true, but unless he can demonstrate that his “careful and extensive study of the data” occurred prior to any personal commitment to the doctrines or the community of his faith, his declaration of pure objectivity rings hollow. Everyone’s perceptions of themselves, the world around them, and their place in it are filtered through interpretive lenses that are overwhelmingly curated by our experiences and our social and ideological identities, and almost unilaterally without our awareness, much less our approval. As an example, the image below should look like two images of different shades of gray.

If you use your finger or some other object to cover the shadows and highlights were the two objects join, you should be able to see that they’re actually the exact same shade of gray. Why do you perceive them as different? Because your mind interprets the image as objects in space, and you’ve spent a lifetime experiencing such objects interacting with light sources, and your mind has been conditioned to expect an object in a light source to appear lighter than the same object in a shadow. Because that’s not what the image shows, our minds just revise our perceptions in the direction of what they expect. Our subconscious minds rifle through every last piece of cognitive mail we will ever receive before we ever see it. We can only ever experience the world our minds allow us to experience.

This holds true for all our senses as well for how we think and reason, and when our social identities, our sense of self, our livelihoods, and our destinies are entangled with religious dogmas, our subconscious minds are going to nudge us (without our awareness or approval) in the direction of interpretive biases that favor whatever protects or advances those dogmas.

We all have biases. We can either openly acknowledge and then confront them, or we can just pretend they don’t exist. McLatchie seems to prefer the latter route. The reality is that apologetics by its very nature presupposes the conclusions for which it argues, and McLatchie openly identifies as an apologist. In other words, the high reliability of the Gospels and Acts is precisely the premise of the argument, but it’s rhetorically useful to assert that it’s not, so it seems to me that’s precisely what McLatchie is doing (more on that below).

Next, McLatchie suggests my insistence that the resurrection is a dogma and not something that can be shown from the data is essentially “resurrecting David Hume’s objection to justified belief in miracles.” Neither my work nor my epistemology is confined to the accomplishments of 18th-century philosophical enquiry, of course, but McLatchie imagines that another 18th-century philosopher’s objections to Hume somehow adequately engage my concerns, so he quotes William Paley to the effect that miracles exist “to vindicate divine messengers,” and therefore we should expect them to deviate from “the way nature normally behaves when left to itself – otherwise, they would be robbed of their evidential value.”

While I would quibble with the notion miracles exist entirely and exclusively to vindicate divine messengers, if that claim is accepted, then miracles only function as such to those who actually witness them, since that vindication is a function of the actual experience of that miracle. Once the miracle is transmitted through someone else’s reporting, the miracle becomes the message, which itself stands in need of vindication. The strength of the miracle as vindication is subordinate to the reliability of the messenger.

It was actually a central part of Paley’s argument that we needed to rely on the historical reliability of these accounts because of the integrity of the evangelists and their willingness to die for their testimony. Such arguments are no longer considered particularly strong by scholars, since scholars generally agree that the Gospels do not represent eye-witness testimony (which itself has been shown by decades and decades of research to be quite problematic).

Additionally, the notion that if miracles are real, we should expect them to violate natural law, is not actual evidence that miracles are real, it’s just an attempt to gin up the expectation that the data should be exactly as we find them, effectively exempting miracles from falsification via the methods of critical enquiry. But there’s a side-effect of this rhetorical prophylaxis. If we should expect miracles to conflict with the methods of critical enquiry, then any claimed miracles that conflict with those methods becomes exempt from them. All miracles are equally likely and equally unfalsifiable.

When it comes to miracles that McLatchie hasn’t already chosen to accept, of course, this is unacceptable. In 2012, he published a blog post that ruminated on a run-in with some Mormon missionaries who countered his objections that Mormon truth claims were thoroughly precluded by archaeological and other data by telling him he need only pray for confirmation from God. This wouldn’t do for McLatchie, who insisted any positive outcome from such a prayer would just be the placebo effect. He continued, “By framing their worldview in this untestable – non-falsifiable – manner, they essentially remove it from the intellectual chopping block.” His post concluded, “it is my contention that faith . . . ought to be justified by evidence. Without such an epistemology, I can see no way to differentiate truth from falsehood.”

So it seems whether or not a claim to miracles belongs on the intellectual chopping block or should be exempt from it comes down to whether or not McLatchie has already chosen to accept that claim to miracles. If he has, demands for empirical data that support the probability of those claims are just misguided attempts to resurrect Hume. If he hasn’t, he makes precisely those demands.

McLatchie’s next section makes the case that because the Gospels are “substantially reliable,” we ought to err on the side of harmonizing apparent discrepancies, as long as those harmonizations are plausible. I have two concerns with this reasoning: (1) the notion that the Gospels are “substantially reliable” is, of course, not demonstrated, because there’s really not a good case to make for it, and (2) there is no plausible way to harmonize the four different accounts of the resurrection. The rest of this post should adequately demonstrate concern #2.

Next, McLatchie offers a brief defense of the notion the numbers of angels mentioned in the different gospels is not a problem. The foundation of this defense is the notion that a narrative that describes two women walking into a tomb and seeing one man sitting on a bench does not necessarily contradict another narrative that describes two women walking into a tomb and suddenly discovering two men standing beside them. His exact words are “if there are two, it is also true to say there was one (no text indicates there was only one).” The idea is that mentioning one doesn’t necessarily mean there wasn’t a second. Additionally, the men could have risen from their seated position “in the course of the events.”

I cannot take seriously the notion this is a plausible defense. This is the very climax of the narratives of the Gospels, and this argument basically requires that the narrators be reliably accurate but also profoundly incompetent. If two women enter a tomb expecting to find the recently deceased body of their beloved Messiah, and instead find two supernatural beings in the tomb with them, a narrator should mention that there were two of them. One divine visitor is definitely noteworthy, but two divine visitors is significantly more noteworthy. The argument that one is not necessarily exclusive of two carried to its logical end would mean that two is not necessarily exclusive of any other number above two, and that any time someone reports seeing a single anything, we could plausibly insist they saw any number of iterations of that thing. None of the Gospels insist there was only one figure because the Gospel authors wouldn’t have a reason to go out of their way to deny the presence of more than one figure unless there was a competing narrative. A narrator who mentions only one divine being even though they knew there were two divine beings is being profoundly negligent. McLatchie says, “Matthew and Mark simply spotlight the angel who spoke and omit mention of the other, who presumably did not speak,” but Luke explicitly says both of them spoke, since the verb eipan is a third person plural verb that means “they said.”

The content of their speech is also quite distinct. Mark has the young man say, “Do not be alarmed; you are looking for Jesus of Nazareth, who was crucified. he has been raised; he is not here. Look, there is the place they laid him. . . .” Meanwhile, Luke has the two of them say, “Why do you look for the living among the dead? He is not here but has risen. . . .” They didn’t say both things exactly as each author reports, so at least one of the accounts of their speech is wrong.

That brings us to their posture. Mark says “they saw a young man sitting on the right side.” This means that at the moment they saw the young man, he was sitting. Luke says that they didn’t see Jesus’s body in the tomb and were perplexed by this, when suddenly (the author uses idou, a deictic narrative particle that is frequently translated “behold” or “look” and draws attention to what follows) there were two men standing by them. The verb for “standing” used here means “to stand at or near a specific place,” and BDAG explains that it often includes a “connotation of suddenness” (listing this passage as an example of that sense). The women were immediately terrified. The narrative cannot plausibly be read to indicate the two women saw either of the men sitting first, only to have one or both of them rise to stand beside them. Mark says the young man was sitting when they saw him. Luke says there were suddenly two men standing beside them as they were perplexed by the absence of Jesus’s body. The narrators are either bafflingly incompetent – in which case one or both of their stories are inaccurate – or they’re just telling different stories.

Just these two issues of number and posture in just these two Gospels of Mark and Luke cannot be plausibly reconciled. Could you argue it’s not impossible that these two narratives are both accurate accounts of the same actual historical event? Sure, it’s not impossible, but McLatchie’s claim was that we err on the side of harmonization where it’s plausible, and in this case, it’s just not plausible. But because McLatchie is dogmatically committed to the harmonization of the Gospels, though, his judgment is going to be skewed and he’s going to feel that it’s perfectly plausible. This is your brain on dogmatism.

McLatchie next takes issue with my identification of apologetics as primarily being concerned with performing conviction and confidence for a non-expert audience that already agrees and just needs to be made to feel validated in that belief (and so doesn’t need a particularly strong or even legitimate argument). For McLatchie, apologetics “done properly, is what one engages in after the results of a fair and balanced open-ended inquiry are in and the time has come to articulate your conclusions, and the justification of those conclusions, to the scholarly community and wider public.” I have no doubt that’s how McLatchie envisions apologetics, but if that’s what it is when done properly, no one’s ever done it properly.

Now, McLatchie disagrees with my assertion that the Gospel of Matthew describes the women seeing the angel descending and opening the tomb. He insists that kai idou just means “and behold,” and shouldn’t be understood to indicate a sudden event witnessed by the women. He further argues that the aorist participle katabas should be interpreted as a pluperfect and translated “an angel of the Lord had descended.” It’s certainly plausible that the story explains that there was an earthquake that result of an angel descending and rolling open the tomb and sat on the stone, only to have the women approach while the angel was sitting on the stone, but in addition to the fact that this interpretation leaves some problems of its own, it cannot plausibly be reconciled with Mark and Luke.

To begin, the women were introduced prior to the events that resulted in the earthquake. If they did not witness the angel descending, then who was the eyewitness who saw it and then reported it to the author of Matthew? If the author of Matthew is telling the story as it was reported to them by eyewitnesses, the angel’s descent will have had to have been witnessed by somebody who reported it to the women so it could be passed on to the author of Matthew. Additionally, there is a narrative purpose to the women witnessing the stone being rolled away. If they come upon the already open tomb with unconscious guards, an angel, and a missing body, somebody could have plausibly absconded with Jesus’s corpse. By having the women witness the opening of the tomb that is already empty and was under supervision until that opening, there is no other explanation for the absence of Jesus’s body than the resurrection.

I think the better reading has the women witness the descent of the angel, but even if it doesn’t, the women first encounter the angel while outside the tomb. The angel is neither standing nor sitting inside the tomb, they are outside the tomb and is the one who directs the women to look inside the tomb. This flatly contradicts the accounts in Mark and Luke, which have the women at least look into the tomb before they perceive the presence of an angel. The Gospel of Matthew also no angel or angels sitting or standing inside the tomb.

McLatchie denies that the account requires the women encounter the angel outside the tomb, but I don’t see a plausible alternative. The angel who is sitting (imperfect aspect, meaning ongoing action) on the stone and speaking to the women cannot be inside the tomb. McLatchie’s account must have the women obliviously walk right past the divine being with an appearance like lightning and clothing as white as snow sitting on the stone outside the tomb, walk into the tomb to the place where Jesus’s body had been laid, then have the angel hop down and join the women in the tomb to tell them not to be afraid and then to come and see the place where Jesus’s body had been laid. That’s entirely neglecting what is actually in the narrative in order to read multiple things absent from the narrative into the narrative between the lines. This is not a plausible harmonization.

Next, McLatchie takes issue with my observation that the preparation of the spices is contradictory between the different accounts. He starts of by insisting Luke 23:56 doesn’t necessarily mean the spices were prepared before the sabbath, but this is a ridiculous argument. The verse follows after an explanation that the women went to the tomb and saw how his body was laid, then continues, “and returning, they prepared spices and ointments. And on the Sabbath they rested, according to the commandment.” The narrative progression makes quite clear they prepared the spices prior to the Sabbath, as all commentators agree.

Acknowledging that one might reasonably understand this to be the intended progression of events, McLatchie insists the texts can be harmonized by just imagining that Joanna already had spices at her house that she prepared at home prior to the Sabbath, while the two Marys and Salome purchased them after dawn. The author of Mark only ever mentions the two Marys and Salome, though. They don’t identify anyone else joining up with these three women to visit the tomb. Luke also mentions all the women who went to the tomb taking “the spices that they had prepared.” There’s no mention of anyone else who showed up with spices they had just purchased. While this is not an impossible harmonization, it certainly isn’t a plausible one, and it continues to indict the Gospel authors as incompetent and negligent storytellers.

Luke and Mark also seem to disagree on when the women came to the tomb. Mark 16:2 says they were on their way when the sun had already come up. The verb used in reference to the sun is an aorist, meaning the action of the sun rising was completed when they were on their way. John 20:1 says “it was still dark.” Luke 24:1 says it was “early dawn.” In my video, I address John and then say, “wait a minute, the other account said the sun had risen. It was dawn.” Here I’m referring back to Mark, which says the sun had risen, but McLatchie only brings up Luke, and goes on to say that John and Luke can be harmonized, since “It is not at all implausible to think that at early dawn it would still be somewhat dark.” That’s absolutely true, but I didn’t refer to Luke, who doesn’t say the sun had come up. I was referring to Mark, which does not say it was early dawn, but quite clearly says “the sun had risen.” McLatchie dismisses this point as “the weakest of McClellan’s examples,” but that’s only because he’s either intentionally or unintentionally misrepresented it.

Regarding the fact that the account in John wildly diverges from the Synoptic account, McLatchie insists that there is no contradiction, since the two sets of texts are describing entirely “separate and independent events.” I don’t think this is remotely plausible, in no small part because John’s account quite explicitly has Mary come upon an open tomb all by herself and then run and get Peter and John before ever encountering any angel, which flatly contradicts the Synoptic accounts, which all have Mary Magdalene encountering the open tomb for the first time with other women and then encountering at least one angel before leaving. But I’d be happy to see McLatchie attempt to demonstrate otherwise by constructing a plausible sequence of events that incorporates every verse of the four different accounts.

McLatchie concludes by suggesting I’ve not looked very hard if I’ve never seen a serious attempt to harmonize all the different accounts, and suggests I check out John Wenham’s book, Easter Enigma, for just such an attempt. But John’s book is full of the same biased attempts to gin up a convoluted tale lying behind all four accounts that doesn’t even come close to being accurately represented in any of the four Gospel accounts. The angels are turning invisible and then visible and then invisible all over again. Details from one account are being arbitrarily read into every nook and cranny of every other account that doesn’t explicitly deny the presence of those details. Matthew’s angel just hangs out on the stone until the guards evidently come to and run away (nobody being around to witness any of this), and then enters the tomb and turns invisible when the women arrive show up, only to turn invisible after they’ve entered the tomb to see that Jesus was not in the place where his body was laid. Then, obviously, the angel tells them to “come and see the place where Jesus’s body had been laid.” Oh, yeah, also, Luke didn’t say the angels were standing by the women, it just says they suddenly appeared to the women. Then they turned invisible when the women left so that Peter and John wouldn’t see them, only to turn visible again when Mary Magdalene looks inside the tomb. The notion this is a plausible harmonization of these significantly divergent accounts of the resurrection is laughable unless one’s entire worldview demands these accounts be reconcilable. For folks so dogmatically committed to inspiration and univocality and some brand of inerrancy – and only for those folks – you’d have to be hopelessly biased not to think it makes all the sense in the world.

McLatchie’s apologetics are just as mired in uncritical dogmatism and bias as any internet apologist’s.

Since you are talking about Resurrection accounts, what do you make of Mark and Matthew, where the holy women to go back to Galilee where Jesus awaits them? In other words, why don't you go back where you came from...? This is contradicted in ACTS, where the disciples are told to stay in Jerusalem...? The Mark story, specifically, would seem to support the body stolen by the Pharisees so Jesus's tomb would not become a shrine...

Here's what I want to know. Have we misread Jesus’ last week in Jerusalem. He gathers a crowd wherever he goes, and he goes and trashes the money-changers in the temple. But that would be a really dramatic gesture--the Jews had been a captured people for hundreds of years--they had no civil authority--only the priestly class, and profiting from religious sacrifices was widely practiced by priests among many cultures, and was often their primary source of income. This would make Jesus a cultural insurrectionist. He didn't need Judas to pick him out in a crowd.